Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 643

Contexto Internacional

vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380200006

Steeves & Ouriques

Energy Security: China and

the United States and the Divergence

in Renewable Energy

Brye Butler Steeves

*

Helton Ricardo Ouriques

**

Abstract: Historically, great powers have gone to great lengths to guarantee the energy necessary to

compete in the international system. Today, as fossil fuel sources diminish and energy demands in-

crease, the most powerful States, specically China and the United States, are competing for energy

resources, including renewable energy sources, while continuing to protect and procure remaining

nonrenewable sources around the world. As such, this article’s goals are: 1) to oer a brief overview

of energy security; 2) to present a brief overview of the energy scenarios of China and the United

States; 3) to show that China is investing more in renewable energy than the United States due, in

part, to the domestic endowment of shale gas of the latter, and the imperative need to diversify the

energy sources of the former.

Keywords: China; United States; Energy Security; Renewable Energy.

Introduction

is article examines the eorts being made by China and the United States to maintain

and improve their respective energy security, highlighting the incorporation of renewable

energy sources. Historically, the world’s greatest powers went to great lengths to guarantee

the energy necessary to be able to compete in the international system. Today, as fossil fuel

sources diminish and demand for energy grows, the most powerful states, including the

two aforementioned, are competing for energy resources (including renewable sources),

while they continue to protect and acquire the world’s remaining fossil fuel sources. Be-

cause energy security is necessary for power, states use energy to guarantee national secu-

rity and grow their global standing. Energy, therefore, has a central role in the structure,

consolidation, and survival of states. e strategies, competition and, principally, the mo-

tivations of actors to protect and obtain energy resources can be analyzed through the re-

* Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), Florianópolis, SC, Brazil; bryesteeves@gmail.com.

** Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), Florianópolis, SC, Brazil; helton.ricar[email protected].

644 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

alist paradigm, which explains the interaction between natural resources, power-seeking

behavior and interstate conict.

us, when it comes to the theme of energy in the international scene, a big part of

the literature adopts a geopolitical, realist theoretical focus. e general assumptions are,

in sum: 1) control of and access to natural resources are fundamental for national power;

2) energy resources are rare; 3) competition between states for resources is growing; and,

4) conicts for resources are probable or inevitable (Dannreuther 2010: 3).

e realist paradigm suggests that interstate competition can result from: national

defense strategies that protect energy resources; states’ energy supplies and routes, and ac-

cess to and control of resources. erefore, countries are motivated by power and always

engaged in a ght to increase their capabilities. State behavior is a product of competition.

However, this behavior can also be a product of socialization. In other words, states follow

norms because it is advantageous for them, or because these norms become internalized.

Furthermore, states are seeking security in anarchy because the main threats come from

other states (Elman 2010). In other words, state behavior is driven by survival and power,

and energy resources are elements of maximizing this power (Cesnakas 2010).

Here we adopt the viewpoint of Michael Klare, an expert in the theme of energy se-

curity who, in his books and articles, argues on behalf of state competition for access to

and control of energy resources, including sources of renewable energy. In his more recent

ndings, Klare states, ‘like the large resource companies, the world’s major powers will

also be forced in the coming years to compete more aggressively in the race for what’s le’

(Klare 2013: 218). However, this aggressive competition can be qualied by cooperative

strategies betwen states, also discussed by the authors. Besides this, the incorporation of

renewable energy resources can be seen as a ‘race for adaptation.’ And, in this regard, ac-

cording to Klare (2013), China has not made a secret of its determination to be a domi-

nant force in the green technology eld. In light of the declarations from the memebers

of the U.S. government and studies from the PEW Charitable Trusts and the American

Energy Innovation Council (AEIC), the authors point out that the United States faces

challenges within the renewable energy area.

From the systemic perspective, as put forth by Giovanni Arrighi

1

and Immanuel

Wallerstein,

2

the current situation of the capitalist world economy is marked by the slow

hegemonic decline of the United States. It is in this scenario that the rise of East Asia (and

of China, in particular) should be understood as more and more central to the process

of capital accumulation. us, the incorporation and development of renewable energy

sources appear the most relevant for China as an important indicator of its rise and, at

the same time, one of the elements that can empirically prove the argument, of these two

aforementioned authors, about the United States.

ese brief assertions are the theoretical basis of this article that intends to show and

explain the dierence in intensity between China and the United States in the incorpo-

ration of renewable energy. During the 2000-2010 period, China surpassed the United

States as the world’s largest energy consumer and largest investor in renewable energy.

is period also provides statistics from the following data sources: ocial documents

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 645

from the Chinese and U.S. governments; a comparison of a sample of energy policies from

the two countries from the Pew Charitable Trusts foundation and the U.S. Energy Infor-

mation Administration (EIA); and, an analysis of energy documents of the International

Energy Agency (IEA), which is an autonomous organization dedicated to the study of

energy. ese are the sources of the data presented throughout this article.

e energy policies and energy consumption of China and the United States, as well

as their respective energy landscapes, are presented in order to meet the aforementioned

primary objective of this article. e rst section presents the importance of energy for

China, the United States and the international system through the use of information

from ocial organizations and statistical data from 2000 (which are fundamental for the

development of the general arguement throughout the text). e text also oers a reec-

tion of the energy security theme and renewable energy, which can be an element to main-

tain power (the United States) or seek power (China).

The importance of energy for China, the United States and the

international system

Energy is power. From a political, economic and environmental viewpoint, energy secu-

rity is one of the most important issues faced by all countries in the world. As such, energy

has a fundamental role in states’ structure, consolidation and survival. Besides this, energy

is an important aspect to be able to understand competition in the international system.

Considering the competition between states, energy is a crucial factor in the distribution

of world power. erefore, those countries with the most control of energy resources have

the biggest power advantage in the international system (Kerr 2012).

States’ ability to control energy directly inuences their capacity to transform energy

resources into wealth and power. e term ‘energy secuirty’ means that energy sources

are sucient to meet the energy demands of a political community, which include social,

economic, and military activity, and that this demand will be met in a reliable, stable man-

ner in the future (Raphael and Stokes 2010). ere are various degrees of energy security

with diering consequences for countries. In general, when demand is not met, citizens’

daily needs, including healthcare, education and transportation, among other quality-of-

life issues, can be aected (Kerr 2012). On a much larger scale, countries can be aected

militarily and economically.

Today, energy security is an important political issue due to the rapid industrial-

ization of the world, growing populations, high levels of consumption and a signicant

dependence on non-renewable fossil fuels. Major powers are going to great lengths to

establish and guarantee their energy supplies. More and more, they are militarizing their

approach to energy security, as evidenced by the United States’ involvement in the Iraqi

invasion of Kuwait in the 1990s; the 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent removal of then

dictator Saddam Hussein.

China is still considered a developing country. However, because it is becoming the

epicenter of the process of capital accumulation, this country has become the world’s lar-

646 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

gest consumer of energy resources and seems to be looking agressively for sources of ener-

gy, as evidenced by its bilateral agreements for oil outside the global market. Besides this,

China and the United States have been competing for some time for oil in the Caspian

Basin, concentrating their respective armed forces and economic resources there, while

trying to minimize the other’s inuence in the area (Raphael and Stokes 2010). Clear-

ly, energy security is inserted into countries’ external policies, just as their international

actions for its aquisition and protection. Why? First, energy ensures survival by meeting

the needs of citizens, and secondly it advances states’ pursuit of global power because it

supplies armies, facilitates economies, and forges alliances. A country’s development and

advancement depend on energy (Kerr 2012).

Just as China and the United States have long competed for fossil fuel resources, these

two great powers are competing to incorporate renewable energy sources to diversify their

respective energy security matrices. is competition between states is intensied by the

decline of U.S.

3

hegemony and the rise of the Chinese economy, as the two compete for

a position of global power. Both China and the United States are turning toward the in-

corporation of renewable energy. Although renewable energy has become a more specic

preoccupation of national energy policies for these two countries, it represents a large part

of China’s national energy consumption and investment, which has a renewable energy

investment of more than 30 percent greater than that of the United States (PEW 2014).

It seems China is incorporating renewable energy at a faster pace than the United

States, due in large part to its high consumption of native coal, which is the primary

energy source of the country’s environmental degradation. Additionally, coal is a non-

renewable resource that is estimated to be depleted by mid-century. In terms of energy

security, China does not have a choice. It must incorporate alternative sources into its

energy matrix. Furthermore, China has thus far not been able to replicate the sucess of the

United States’ shale gas extraction, known as fracking.

However, China has sucient renewable natural resources (specically wind and sun)

to potentially meet its future energy demands. Meanwhile, the United States is in the mi-

dst of a natural gas boom as a result of its success in shale extraction, which could supply

the country with energy for millions of years. While the United States is the world’s second

largest investor in renewable energy, its investments year aer year are dwindling and, at

the same time, its extraction of shale gas is growing signicantly. It is acknowledged here

that there are many factors that contribute to the incorporation of renewable energy, such

as economic gains (new jobs associated with the development of renewable resources and

their export potential); environmental degradation (pollution and CO

2

emissions result-

ing from the use of fossil fuels); depletion of non-renewable resources (remaining known

sources, such as oil, will be unable to meet future energy demands); and political motiva-

tions (desires of governments to globally lead clean energy movements), among others.

e eects of energy use by China and the United States are far reaching, impacting

the world’s markets, economies, environment, public health, and interstate relations. It is

also important to mention the relationship between these two countries, the signicant

implications for global energy, as well as the renewable energy divergence between China

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 647

and the United States. ey share common energy challenges, but still do not cooperate

signicantly in addressing energy issues. e Sino-American relationship, in general, is

characterized by inherent dierences and distrust of one another, while further challenged

by China’s economic growth and the relative economic decline of the United States. us,

there is potential for conict as seen through energy competition for non-renewable and

renewable sources. What’s more, the risk of violence is omnipresent when material re-

sources are perceived as necessary for national security because governments will respond

to threats with military force (Klare 2000: 300).

In fact, the lack of cooperation in addressing common energy security problems

(Zweig and Jianhai 2005) is a form of conict, although war between the two seems un-

likely because of their interdependent relationship, which is globally and historically un-

precedented. China and the United States have become interconnected, each counting on

the other for its economic health: China is highly dependent on U.S. export markets and

U.S. Treasury bond markets for its foreign reserves, and the United States greatly depends

on low-cost imports from China, as well as Chinese nancing of a signicant part of the

U.S. budget and decits (Ho-Fung 2009). However, this interdependence has not, so far,

extended much into the realm of energy security, where China and the United States ap-

pear quite competitive. Historically, powerful, capitalist states promoted new strategies

and structures for the accumulation of capital and power on a global scale that eventually

were emulated by peripheral and semi-peripheral actors. ese strategies and structures

included business related to the acquisition, production, distribution and consumption

of energy. In short, states were motivated by power, and energy was used as a channel to

enforce the power.

To understand energy’s vital role in the international system, it is important to analyze

the relationship between energy and state competition as well as actors’ behaviour. Con-

sidering the competition between states as well as state behaviour, energy is an important

factor in the distribution of global power. Due to the fact that energy is necessary for

states’ self-survival, those states that control energy have a power advantage in the interna-

tional system (Kerr 2012), which results in competition between states. As energy demand

from the world’s great powers grows, the supply of non-renewable energy is diminishing.

is greatly intensies competition for the remaining known supplies of fossil fuel sources

as well as for the incorporation of alternative fossil fuel sources. e competition for ener-

gy sources also seems to be leading to new energy development eorts – as conventional

energy prices continue to rise, so does the interest of states for alternative energy sources

(Podobnik 2002).

Meanwhile, the world’s major powers inuence those on the perifery to include re-

newable energy as they seek energy security. All states appear to be acting in an eort to

maintain or increase their overall positions of power. e competition among states af-

fects energy policies through causal relations: 1) material power is needed for states, at a

minimum, to able to ensure their own survival and, at a maximum, obtain global power;

2) the accumulation of material resources, including energy resources, is needed for a

global position of power in a capitalist economy and especially under a hegemonic transi-

tion; and, 3) hegemonic transitions lead to innovation and competition in energy policies.

648 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

Policies and Energy Consumption in China and the United States

China and the United States face common energy challenges. Both are large energy con-

sumers. Both need energy to maintain stable, growing economies. Both want to minimize

environmental degradation. Both seek to diversify their sources of energy for energy se-

curity reasons. And today, both these great powers nd themselves in an unsustainable

situation based on implications that their fossil fuels consumption have for themselves

and the rest of the world.

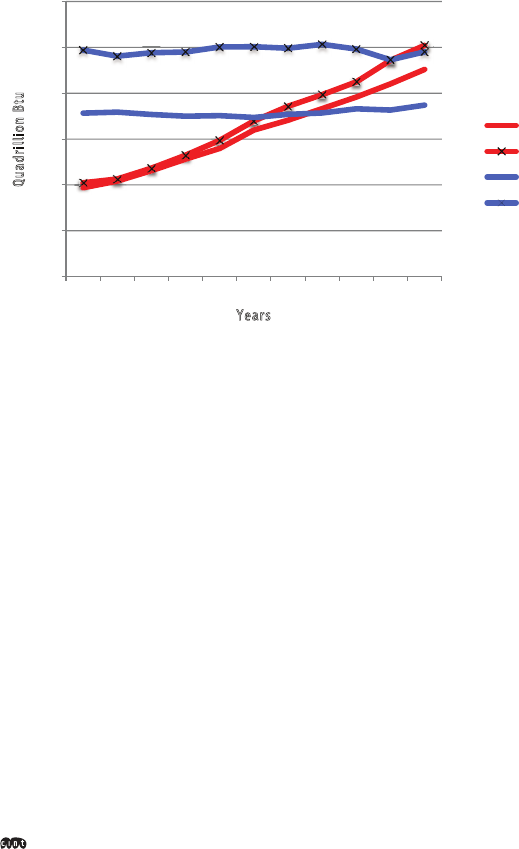

Figure 1 – Total energy production and consumption

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Quadrillion Btu

Years

China Production

China Consumption

U.S. Production

U.S. Consumption

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (2014).

As shown in Figure 1, China surpassed the United States in 2010 as the world’s largest

energy consumer (U.S. EIA). China’s demand for all forms of energy has risen, and is pro-

jected to continue to rise, due in large part to the production of export goods and materi-

als for local construction projects. Coal is the dominant source of energy in China (IEA

2007b). Like China, the United States is also almost completely dependent on fossil fuels as

its primary energy source. And also like China, the United States is self-su cient in coal and

heavily-dependent on imported oil. It is projected that U.S. energy demand will continue

to increase in light of its population and economic growth. e latter is primarily driven

by heightened demand in the residential and transport sectors, although all areas show an

increased demand (IEA 2007a: 15).

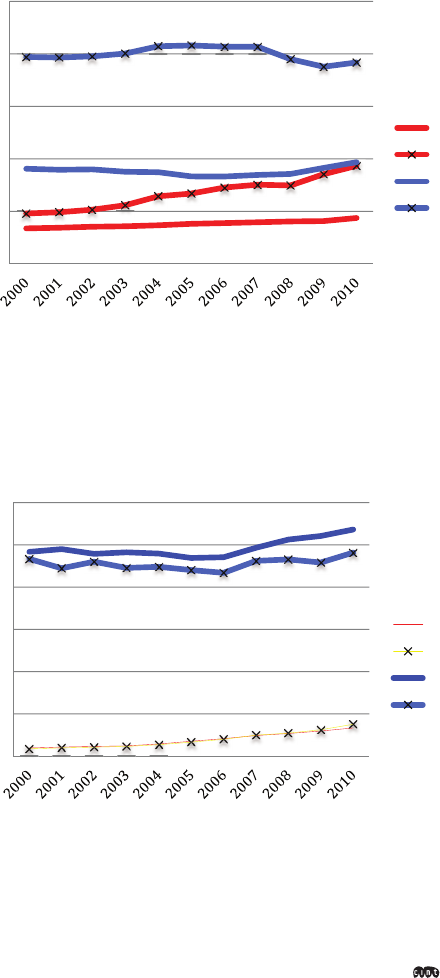

A comparison between the two countries shows that both use more oil than they

produce. In 2008, U.S. oil consumption fell slightly and remained as such until 2010. In

China, oil consumption has increased year a er year during this same time period (Figure

2). From 2000 to 2010, the United States produced more natural gas than it consumed,

while the supply and consumption of natural gas in China was more or less balanced

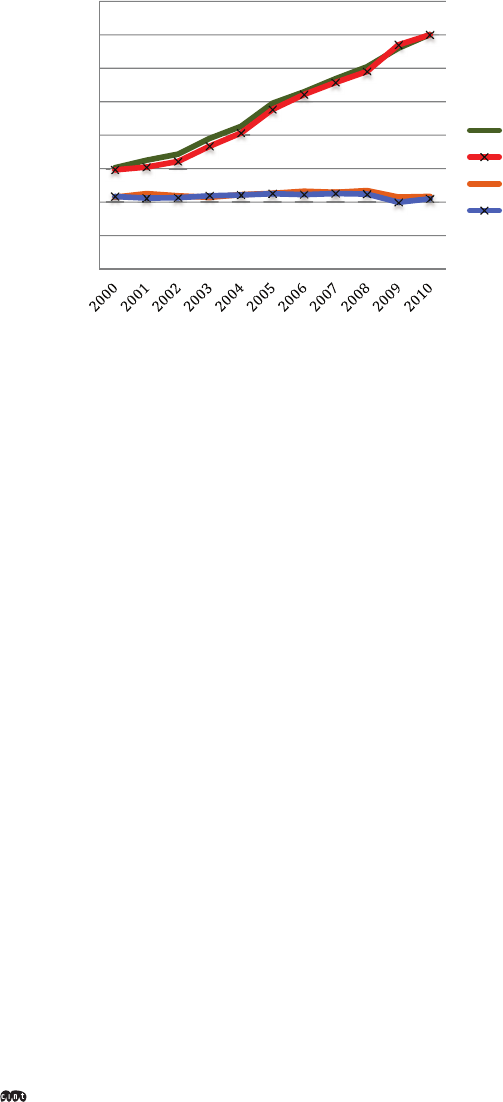

during this period (Figure 3). For both China and the United States, coal consumption is

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 649

broadly in line with the amount each country produces, but the volume of coal consump-

tion in China far exceeds U.S. coal consumption. In addition, Chinese coal consumption

increased year a er year during the 2000-2010 period, while U.S. coal consumption re-

mained mostly constant (Figure 4).

Figure 2 - Oil demand and production

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

Millions of barrel per day

Years

China Supply

China Consumption

U.S. Supply

U.S. Consumption

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (2014).

Figure 3- Natural gas production and consumption

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

30000

Billion of Cubic Feet

Years

China Production

China Consumption

U.S. Production

U.S. Consumption

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (2014).

650 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

Figure 4 – Coal production and consumption

0

500000

1000000

1500000

2000000

2500000

3000000

3500000

4000000

Millions of Short Tons

Years

China Production

China Consumption

U.S. Production

U.S. Consumption

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (2014)

rough their respective energy policies and public rhetoric, both countries have

identi ed the need to incorporate renewable energy sources in their energy matrix, driven

by economic, environmental, political, and cultural factors (Gallagher 2013). In addition,

although less than 10 percent of energy consumption in both countries is derived from

renewable sources (U.S. EIA), the two powers seem to be competing to lead the world in

the development and use of renewable energy. But, China has a wide lead in the race for

clean energy (PEW 2014: 4). Since the middle of this decade, China has gone from being

a relatively small player in renewable energy to becoming the ‘clean energy superpower of

the world’ (PEW 2014), both in investment and use. Holding the top spot for several years,

China invested 54.2 billion dollars in renewable energy and in 2013 had 191 giga watts of

renewable energy capacity. In a distant second place, the United States invested 36.7 bil-

lion dollars and in 2013 had 138.2 giga watts of renewable energy capacity. In other words,

China has invested 38.5 percent more than the United States and claimed a renewable

energy capacity 32.1 percent higher than the United States (PEW 2014: 37, 50).

As stated by PEW (2014: 13-14), ‘China’s e orts to reduce poverty and increase access

to energy, keep up with rapid economic development, and combat severe air pollution in

its major cities have driven its rapid rise to the front of the world’s clean energy.’ During

the past ve years, China’s investment in renewable energy grew at a compound annual

growth rate of 18 percent. is level of investment has fuelled the adoption of renewable

energy, leading to record developments in the implementation of wind farms, solar energy

and small capacity hydroelectric power plants. us, ‘with ample production capacity in

the solar and wind sectors, growing domestic markets and unparalleled national targets

for renewable energy, China is prepared to lead the world’s clean energy market for many

years’ (PEW 2014: 13, 14).

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 651

At the same time, the United States’ incorporation of renewable energy has stagnated,

falling nine percent in 2013, likely due to, at least in part, the near-compliance of state

renewable energy portfolios and a lack of development of a national energy policy. Ana-

lysts indicate that the U.S. renewable energy market has long-term resilience, (PEW 2014:

15), although others worry that the use of renewable energy is threatened by the country’s

expansion of shale gas (Harvey 2012).

e competitive eorts of China and the United States for energy security also have

implications for their respective technological advances and related economic gains. For

example, in China the ‘eorts to dominate renewable energy technologies’ have made it

the largest producer of wind turbines and solar panels in just a few years (Bradsher 2010),

while at the same time have increased the energy, economic, and environmental risks for

its American competitor. In his 2010 State of the Union speech, President Barack Obama

said, “... the United States was falling behind other countries, especially China, on energy”

(Bradsher 2010) and he also declared that the United States must “win the future” through

the renewable energy race (Murray et al. 2011).

Why is the United States falling behind China in its investment and incorporation

of renewable energy sources? It seems that the dierences in the allocation of natural re-

sources of the two countries, both fossil fuels and renewable sources, could be driving the

pace of each country’s movement toward clean energy. It is recognized that many factors

contribute to the divergence between China and the United States, including political,

economic, and cultural factors, although this analysis focuses mainly on the allocation of

natural resources and domestic consumption.

China’s energy landscape

China is the world’s largest energy consumer, second largest economy and most populous

country with 1.3 billion people. China’s economy has experienced unprecedented growth

during recent decades to become a global economic superpower. At the same time, it

holds the title of world’s biggest polluter. Its era of energy independence and self-sucient

ideology has ended, replaced by its voracious appetite for energy, which is both the cause

and consequence of its fast-growing economy. Today, the success of China’s economic

growth is inseparable from its dependence on global markets of the capitalist world.

Chinese economic growth over the past three decades has been based on energy con-

sumption, which has exceeded its GDP growth since 2002 (Xing and Clark 2010). China

soon became dependent on energy imports, and in 2010 surpassed the United States to

become the largest energy consumer in the world. Increasingly, China’s high energy use is

both a cause and an eect of its unprecedented economic growth, particularly in the heavy

industry sector. China’s demand for all forms of energy is largely due to the production

and exportation of goods, and manufacturing materials for construction projects in the

domestic market (IEA 2007b: 261).

China’s energy matrix has the following characteristics:

652 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

Coal: Coal represents close to 70 percent of the country’s total primary energy con-

sumption, although China’s coal sources are low quality, dangerous to mine, highly

sulfuric and extremely polluting (Cornelius and Story 2007). China’s coal reserves

are equivalent to about 12.5 percent of the world’s total reserves, and at current pro-

duction levels, should last until mid-century. Because coal is an abundant, low-cost

native resource, China depends on it as its primary energy source. However, this de-

pendence is the primary cause of China’s energy-related environmental degradation

and is cited as the principal factor in high CO

2

emissions. e country is investing in

technologies in order to use coal in a cleaner manner (Cornelius and Story 2007).

Oil: Crude oil accounts for less than one-quarter of the country’s total energy con-

sumption despite its growing dependence on imported oil, placing it among the main

issues on its political agenda. A key factor behind this is the rapid expansion of Chi-

na’s auto eet. Meanwhile, the country’s reserves are estimated at less than 15 years.

China is the world’s h largest oil producer, but in 2011 was dependent on imports

to meet about 54 percent of its oil demand. Of its oil imports, more than half comes

from the Middle East. ere are four large state-owned Chinese oil companies; the

government regulates the prices for petroleum products (IEA 2012: 6).

Gas: China is a net importer of natural gas; that is to say that although it is a gas pro-

ducer and exporter, its total imports exceed the volume of gas exported. is power

source accounted for only 4 percent of China’s total energy consumption in 2011 (U.S.

EIA). e country is also exploring shale gas extraction possibilities to reach known

sources of gas that it has not yet been able to extract.

Alternative Sources: Hydro, wind, solar and nuclear energy sources form a small

percentage of China’s energy matrix and are being further developed, but not enough

to reduce China’s dependence on fossil fuels (IEA 2007b). However, with its natural

endowments of renewable resources, China could meet all its domestic energy de-

mand (Gallagher 2013).

‘Nowhere is China’s global inuence greater than in energy markets’ (Cornelius and

Story 2007: 7). is applies especially to China’s unquenchable thirst for crude oil, which

has more than doubled since the mid-1990s. Today, the Chinese economy is the world’s

second largest oil consumer, and with the stagnation in domestic production, its growing

import demand is widely seen as a key factor behind the rise in global oil prices. China’s

role in global energy development aects its policy formation and interstate relations,

environmental protection standards, and the energy eciency of other global players

through the goods it produces and exports. Despite the rapid growth of the country’s de-

mand from all sectors of energy, China’s global emergence has made the world economy

become more dependent on oil, via prices, competition for supplies, and safety concerns.

To improve the eciency of vehicles and electrical appliances that China produces and

exports, is to improve energy eciency for the rest of the world (IEA 2007b: 45).

As a rising global power and large energy consumer, China is on a trajectory that

could potentially reshape the global energy landscape. is may be especially true in the

areas of conservation and ecient use of fossil fuels, as well as the subsequent global in-

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 653

corporation of renewable energy sources through China’s own technological advances and

emulation by other countries of its clean energy practices. is potential intersection of

economic and political rise with the global energy markets is reminiscent of the increased

U.S. demand for oil and dependence on imports, which coincided with its growing stra-

tegic power during the 20

th

Century. As China grows economically, it increasingly plays

an important role in determining global technical standards and promoting their conver-

gence. China’s growing weight in the global economy can contribute to revolutionizing the

world’s energy system (Cornelius and Story 2007: 15).

The United States’ energy landscape

e United States is currently the world’s largest economy, although there are projections

of it being topped by the Chinese economy. With a population of almost 314 million, the

United States is the second largest consumer of total energy. e United States is almost

entirely dependent on fossil fuels for its energy supply, and renewable sources account for

only a small portion of its total matrix. Like China, the United States is self-sucient in

coal and heavily dependent on imported oil. Meanwhile, its demand for energy is expect-

ed to continue to increase due to population and economic growth. e latter is driven

mainly by an increased demand in the residential and transport sectors, although all areas

have seen an increase in demand (IEA 2007a: 15).

e U.S. energy matrix includes:

Oil: Most of the United States’ energy consumption, about 36 percent, comes from

oil. e country is heavily dependent on imported oil, due to increased demand in the

residential and transport sectors. e United States is the largest oil importer in the

world, followed by China (Gallagher 2013).

Gas: Natural gas accounts for about 25 percent of the country’s energy consumption.

Energy from shale gas sources in the United States increased by more than 50 percent

annually between 2007 and 2012, increasing total U.S. gas production from 5 percent

to 39 percent. In light of these shale gas developments, the United States is ‘about to

become an energy superpower’ (Blackwill and O’Sullivan 2014).

Coal: Nearly 20 percent of U.S. energy consumption is met by coal.

Alternative sources: About 8 percent of U.S. energy consumption is powered by nu-

clear energy and 9 percent by renewable energy, including solar, geothermal, biomass,

and hydro sources. e Energy Policy Act of 2005 describes the use of clean energy

in the country, especially a strong movement toward nuclear energy (U.S. EIA). e

United States also has signicant renewable energy sources in a way that has the po-

tential to lead the world in renewable energy despite its natural endowment of fossil

fuels. For example, its wind resources could exceed the total of the projected elec-

tricity demand for the entire country, and the conditions for solar energy also look

promising. Of note is that countries with less favorable conditions for renewable en-

ergy, including China and Germany, have approved greater renewable energy policies

(Gallagher 2013).

654 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

Like China, the United States is exerting global inuence over the future development

of energy. e country has served as a global leader in energy research and development,

and has advanced energy technologies. e U.S. government is the largest funder in the

world of energy research and development, which historically has promoted the advance-

ment of all energy elds, including fossil, nuclear, and renewable fuels. e government

partners with private and educational institutions and international organizations to pro-

mote its agenda. e objectives of its policies guide the research and development of ener-

gy technologies. ese investments in research and development are an important policy

tool to meet the country’s energy goals. e U.S. government is also the world leader in

international collaboration on technology and participates in international organizations

focused on energy best practices, such as the International Partnership for the Hydrogen

Economy. e United States has several research and development strategies that coor-

dinate the investments in research and technology development, including the Climate

Change Technology Program, which is an investment program of several billion dollars

for the research, development, and implementation of climate-related technologies. An-

other example, the Advanced Energy Initiative, works to promote energy eciency tech-

nologies and reduce reliance on imports, including investments in cleaner coal plants and

alternative and renewable sources (IEA 2007a: 31, 50).

Energy security and renewable Energy

Non-renewable energy sources provide about 90 percent of the world’s commercial ener-

gy, while nuclear power and hydropower provide most of the remaining amount (Podob-

nik 2002: 253). e problem of energy security can be seen simply as supply and demand:

energy needs are growing and showing no signs of slowing yet, at the same time, known

sources cannot keep up with this pace of growth. Due to the fact that the world’s largest

energy consumers cannot meet their energy needs through domestic supplies, and the

global supply seems unable to meet future demands, we can see a shi towards renewable

energy sources. While this pressure can, and will likely be, mitigated by technological

advances and the discovery of new sources, the shortage resulting from the current rate of

consumption will lead to competition for access and control, which will increase tension

between states (Podobnik 2002).

Both China and the United States are in an unsustainable energy situation. Because of

their current high energy consumption, both countries are almost completely dependent

on fossil fuels, while renewable sources make up only a small portion of the energy supply.

Both countries are self-sucient in coal, largely self-sucient in natural gas and heavily

dependent on imported oil. Meanwhile, energy demand will continue to increase because

of population and economic growth. e latter is mainly driven by increased demand in

the residential and transport sectors, although all areas have contributed to the increased

demand (IEA 2007a: 15).

It is expected that global demand for energy will exceed known sources and most

of the major energy consumers in the world will not have a sucient domestic supply,

especially of oil, to meet this future projected demand. Meanwhile, there is considerable

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 655

political pressure to diversify away from coal consumption because it is considered a ma-

jor source of pollution and a serious danger to public health. However, governments are

also under pressure to promote economic growth in which energy plays a key role. is

means that energy security is deeply rooted in foreign policy and is an important factor in

relations between states. erefore, the most important powers in the world are increasing

their investments in renewable and sustainable alternatives, including solar, wind, and hy-

dropower. Meanwhile, less powerful states seek to imitate the most powerful states in the

world. is is evidenced in some developing nations, like Brazil, India and South Africa,

which try to emulate the clean energy policies of the European Union.

e high energy consumption of both China and the United States is a threat to global

energy security, and therefore one of their most important political challenges seems to be to

develop the ability to meet long-term energy needs reliably, safely, economically, and in an en-

vironmentally friendly way. Common challenges include pollution and environmental degra-

dation, inecient and intensive use of energy, and the depletion of non-renewable resources.

Both countries are addressing these challenges in a similar way, with political goals aimed at

reducing dependence on imports, reducing emissions of greenhouse gases, and increasing

energy eciency. Both China and the United States have implemented the following national

energy policies: carbon cap carbon market, renewable energy standard, tax incentives for

clean energy ecient standards, feed-in taris and green bonds (PEW 2014: 37, 50). Political

action to reduce demand, coupled with increased energy eciency and the development of

new sources, particularly renewables, can be an alternative for these two nations.

ere is an intersection between energy security, national development and states’

policies (Pautasso and Kerr 2008). Most states are challenged by competition for resourc-

es, shortages in energy supply, environmental impacts, and the search for energy policy

solutions to address these challenges and to promote world order. In general, the objec-

tives of energy policy include ensuring energy supply safety, generating economic growth

and facilitating the preservation of the environment.

A comparison of the energy policies and scenarios (energy supply, demand and reserves)

of China and the United States suggests that a change in the energy policies of these states is

critical in order to meet the world’s contemporary energy security needs. While many of the

Chinese and U.S. energy policy solutions are similar, the two countries have little in com-

mon in terms of collaboration or cooperation. ere does seem to be a great opportunity

for cooperation between these states in developing and implementing long-term sustainable

energy policies. e world would benet from energy cooperation between China and the

United States as well as a potential transition to a predominantly renewable energy system.

e eects of clean energy are far-reaching. Renewable energy sources contribute to

energy security by diversifying energy sources, both technologically and geographically.

ey aect the economy through imports, exports, job creation, global energy prices,

public health and environmental degradation mitigation (IEA.org; Gallagher 2013). Both

China and the United States have enough of their own renewable sources to meet all of

their potential demand for domestic energy. In addition, the United States has such a sig-

nicant endowment of renewable energy resources that it could lead the world in renew-

able energy (Gallagher 2013), despite its recent boom in shale gas.

656 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

Fundamental changes in the global energy system occur more easily during the de-

cline of a great power and when the international system is in disarray (Podobnik 2006),

as in the current situation of the relative economic decline the United States and the rise of

China (Arrighi 2008). e role of the accumulation of resources and state power is evident

in hegemonic transition periods, as were the two previous transitions in the 19

th

and 20

th

Centuries. Now, China is emerging as a global economic power in the 21

st

Century. is

hegemonic transition prompts competition and innovation around the globe (Podobnik

2002), not just between the powers in transition. Energy security is no exception. Devel-

oped countries and developing countries spend billions of dollars annually incorporating

renewables into their energy security policies and for the last eight years there has been a

growing trend for larger investments by developing countries.

In recent years, China has led the world in investment in renewable energy, followed

by the United States. Four developing countries were among the 10 largest investors in

renewable energy in 2012: China, India, Brazil and South Africa, four of the ve BRICS

nations. ese nations’ billion-dollar investments place them at the level of major powers,

like the United States, Germany, Japan, Italy, the U.K. and France. Russia, the remaining

BRICS nation, is an exporter of energy that is also incorporating renewable energy into its

national policies. Competition for energy resources also seems to be spurring the develop-

ment of renewable energy as conventional energy prices continue to rise (Podobnik 2002).

History shows that a crisis in a dominant source of energy was mitigated by the transition

to another energy source, such as the transition from coal to oil in Great Britain during

the 19

th

Century. Podobnik (2006) suggests that the inevitable oil crisis today will, in part,

cause a shi towards renewable energy sources.

e last two centuries show two major transitions of power during periods of indus-

trial growth: the shi from charcoal to coal in the mid-19

th

Century, and when oil became

the dominant world energy source in the mid-20

th

Century. Many countries appeared to

be self-sucient in energy until around 1950, when they began to become increasingly

dependent on energy imports, leading to the transition to oil. Due to the fact that the

major powers did not have signicant oil reserves, energy needs were underpinned by

imports. is strategy does not seem tenable for future energy needs and also seems to

be prompting new, and in some cases, more, investments in renewable energy options.

Perhaps the energy transition of the 21

st

Century will be dened by a shi from non-

renewable fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

Hegemonic advancement can be seen during the energy transition periods, including

the transitions of 1750-1850 from peat and charcoal to coal, and the 1900-1950 transition

from coal to oil. Coal and steam power, in combination with capital and empire, increased

ownership and led to an ecological surplus resulting in food, labor, and cheap energy. e

cheap coal, and later (aer 1945), cheap oil led to increased consumption and a signicant

expansion of consumer markets. In addition, cheap raw materials, that is, vital goods such

as food, raw materials, and energy were instrumental in the creation and maintenance of

large waves of accumulation because this ecological surplus reduces production costs and

increases the rate of prot (Moore 2013).

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 657

Today, we see close races for fossil fuels (with the global supply becoming increasingly

limited in the medium- and long-term), while countries seek to diversify their respective

energy matrices to include alternative sources, such as shale gas extraction and renewable

energy to meet their energy needs. It seems that the current global energy system is in

transition, with its unsustainable reliance on the use of fossil fuels, including their exhaus-

tion, pollutant nature, and increased demand, as well as the intersection of three systemic

dynamics identied by Podobnik (2006) as necessary conditions for a shi in global pow-

er. ey are: 1) geopolitical rivalry, 2) commercial competition and 3) social conict. Each

of these dynamics is evident today, as we see: 1) competition for existing limited fossil

fuels in the world, specically oil, 2) economic competition for energy technologies, such

as foreign investment opportunities and the export of renewable energy, and 3) the chaos

that is associated with the hegemonic transition.

In sum, China and the United States are competing for resources, striving for market

share and ghting against environmental degradation caused by the excessive use of fossil

fuels. Now is the time for an energy transition, but whether it will be in the direction of

renewable energy is still uncertain. Moreover, it is necessary to monitor in detail whether

China, which has so far been unable to replicate the shale gas boom in the United States,

will continue to increase its investment in the use of renewable energy sources to help se-

cure its energy security. In other words, it is worth further investigation based on the cur-

rent divergence of investments in renewable energy by both China and the United States.

Final considerations

Concerns about the current state of energy security could trigger deep structural changes

in the global energy system (Cornelius and Story 2007: 14). Renewable energy oers the

long-term promise of sustainability on several fronts for countries around the world (Hei-

man and Solomon 2004). Currently, the world’s energy needs are growing without show-

ing signs of slowing, while at the same time, known sources of non-renewable energy will

not be able to sustain this rate of growth. Although the pressure to meet increasing de-

mands can, and probably will, be mitigated by technological advances and the discovery of

new sources (Cornelius and Story 2007), renewable sources appear to be a viable solution

to contemporary energy challenges for many countries around the world.

As a global power and the world’s highest energy consumer, China is on a path to

potentially reshape the global energy landscape, especially in the areas of fossil fuels con-

servation, more ecient energy use, and the subsequent global incorporation of renew-

able energy sources. is may be possible through China’s own technological advances

and the other countries’ emulation of its clean energy practices. As it grows economically,

China will increasingly play an important role in determining overall technical standards

and in the promotion of energy convergence. Its growing weight in the global economy

could help revolutionize the world’s energy system (Cornelius and Story 2007: 15). Energy

challenges in China are no dierent from other countries with the same problem, but the

extent and speed at which change is occurring is unique. Like other countries, China’s en-

658 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

ergy policy challenges go hand-in-hand with its economic policy objectives. e country

needs to maintain its rapid development and economic growth, but in a much less ener-

gy-intensive way. is is widely recognized by the Chinese government, but signicant

changes in energy consumption relative to economic output could mean major changes in

its economic structure (IEA 2007b: 271-2).

e role of the United States in renewable energy should not be discounted, even if it

is incorporating proportionally less than China in this area. e United States is the global

leader in energy research and development and, furthermore, has always progressed ener-

gy technologies. e U.S. government is the world’s largest contributor to energy research

and development, which has historically provided huge advances such as in the energy

elds of fossil fuels, nuclear power, and renewable sources. However, the abundance of

shale gas and the increasing reliance on this resource may slow the country’s move to-

wards greater incorporation of renewable sources in its energy matrix. Despite its renew-

able energy resources and capacity to meet energy demands with these sources, the United

States appears set to continue its reliance on nonrenewable energy sources because of its

abundant natural endowment of shale gas.

Pautasso and Kerr (2008) state that the new world order should be structured based

on the symbiotic relationship of the rise of China and the United States’ reaction to this

rise. Such a transition could result in a change in the balance of power in the international

system toward China. A major factor in this transition is related to energy security, as we

have seen in previous hegemonic transitions. Stronger cooperation between China and

the United States is vital to address the common challenges of energy security, including

market stability and supply, as well as new advances in renewable energy that benet ener-

gy consumption, boost economies, and mitigate environmental impacts. However, China

and the United States seem to have a long way to go to achieve their respective policy goals

for energy eciency and environmental sustainability. Energy-related relations between

them seem to be characterized by a mixture of cooperation, coexistence and competition.

Renewable energy is oen portrayed as a zero-sum game, but there are reasons for co-

operation (Zweig and Jianhai 2005; Murray et al. 2011). As stated by Murray et al. (2011:

7): ‘It is not uncommon for the terminology to frame the impetus for the development of

clean technologies as a war, with the implication that one country will win and others will

lose...’ However, other countries ‘can also win by having access to cleaner energy and use

energy more eciently than they would normally, even if the technologies that produce

the energy originates in another country’ (Murray et al. 2011).

It is important to stress that relations between China and the United States have been

characterized by interdependence. ese two great powers are both in competition with

each other and mutually dependent on each other in, for example, trade and investments.

As noted by Morris (2012), the interactions between these two countries are complex and

marked by both cooperation and conict. China is highly dependent on the U.S. con-

sumer market for its exports and the United States, in turn, depends on large volumes of

inexpensive goods produced by China as well as Chinese funding for a signicant portion

of its current account decits (Arrighi 2008; Ho-Fung 2009). erefore, it is unlikely that

China will directly challenge U.S. energy supply sources – aer all, it still depends on

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 659

U.S. investments and the U.S. market. Taking this into consideration, this article aims to

show that China is incorporating and investing in more renewable energy resources, quite

possibly with the intent of global leadership in this sector, inclusive of its technological

innovations, as highlighted by Klare (2013).

In regard to the United States, the race for renewable energy incorporation has already

been acknowledged as a challenge by the U.S. government. In 2014, President Barack

Obama announced the expansion of the country’s cooperation with China on climate

change and clean energy (U.S.-China Joint Announcement 2014). Such an announcement

can be understood as the United States’ reaction to China’s prominence in the eld of re-

newable energy, as demonstrated by the data presented in this article. Moreover, as high-

lighted by Klare (2013), the dynamics of the American political process should also be

taken into consideration when considering the country’s investments in renewable energy.

For example, as in the present situation, a U.S. congress with a Republican majority prob-

ably will not authorize more resources and new projects in the renewable energy sector.

3

Because the issue of energy is crucial for the power-capital-accumulation processes,

China’s greater use and development of renewable energy, as presented in this article,

are indicators that this country, which has led East Asia’ as the most dynamic region in

the world economy, also seems to be aiming for world leadership in this strategic sector.

Maintaining or even expanding the current scenario described in this article, the diver-

gence between China and the United States in the development, control of, and leadership

in renewable energy appears to provide empirical evidence of the end of the American

hegemony, defended by Wallerstein and Arrighi.

Although it is too premature to make statements about a new hegemony, China, as

an emerging global power and the world’s largest energy consumer, is able potentially to

reshape the global energy landscape, primarily in the ecient use and conservation of fos-

sil fuels, as well as through the incorporation of renewable energy sources into its energy

matrix. However, as highlighted by Arrighi (2008: 392), ‘inspired by others in the Western

way of excessive energy consumption, China’s rapid economic growth has not yet created

for itself and the world an ecologically sustainable path of development’.

Notes

1 Details are in Arrighi’s works Chaos and Governability in the Modern World System (2001) and Adam Smith

in Beijing (2008).

2 Details of the U.S. hegemonic decline can be found in Wallerstein’s e End of the World as We Know It

(2002) and e Decline of American Power (2004).

3 ‘Any signicant increase in federal expenditures on renewable energy appears to have little chance of winning

approval in the House of Representatives, where anti-spendig Republicans dominate. Likewise, despite the

various report’s recommendations, it seems improbable that Congress will authorize any expansion of the

federal bureaucracy to oversee energy projects of this sort. No doubt some venture capitalists and private

companies will put their own funds into new energy initiatives, but such investments are almost certainly

not going to reach the minimum level that the President’s Council of Advisors identied as necessary for

continued American leadership in clean energy design. And without adequate investment, the council

predicts, America is destined to become a ‘technology taker’ rather than a ‘technology maker’, with the

implied economic and leadership consequences’ (Klare 2013: 233).

660 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

References

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2008. Adam Smith em Pequim. São Paulo: Boitempo.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver. Caos e governabilidade no moderno sistema mundial. Rio de

Janeiro: Contraponto/Editora da UFRJ, 2001.

Blackwill, Robert D. and Meghan L. O’Sullivan. 2014. ‘America’s Energy Edge: e Geopolitical

Consequences of the Shale Revolution.’ Foreign Aairs, March/April. At: http://www.foreignaairs.

com/articles/140750/robert-d-blackwill-and-meghan-l-osullivan/americas-energy-edge [Acessed

on 22 July 2014]

Bradsher, Keith. 2010. ‘China Leading Global Race to Make Clean Energy.’ e New York Times,

January. At www.agriculturedefensecoalition.org [Acessed on 10 April 2014]

Bradsher, Keith. ‘Natural Gas Production Falls Short in China.’ e New York Times [online]. 21

Aug., 2014 [Acessed on 5 April 2014]

Cesnakas, Giedrius. 2010. ‘Energy resources in foreign policy: a theoretical approach.’ Journal of

Law & Politics 3 (1): 30-52.

Cornelius, Peter and Jonathan Story. 2007. China and global energy markets. Elsevier Limited on

Behalf of Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Dannreuther, Roland. 2010. ‘International Relations eories: Energy, Minerals and Conict.’ Polin-

ares EU Policy on Natural Resources. Polinares Working Paper, n. 8.

Elman, Colin. 2010, ‘Energy Security.’ In Colins, Alan (ed), Contemporary Security Studies. New

York: Oxford University Press: 15-28.

Gallagher, Kelly Sims. 2013. ‘Why and how governments support renewable energy.’ MIT Press Jour-

nals 142 (1): 59-77 [online] [Accessed on 5 April 2014]

Harvey, Fiona. 2012. ‘Golden Age of Gas reatens Renewable Energy, IEA Warns.’ e Guardian

[online], May. At www.theguardian.com. [Accessed 10 April 2014].

Heiman, Michael K and Barry D Solomon. 2004. ‘Power to the People: Electric Utility Restructuring

and the Commitment to Renewable Energy.’ In: Annals of the Association of American Geogra-

phers. 94 (1).

Hiscock, Geo. 2013. ‘Global Competition for Energy Resources on Leaders’ Agenda’, Available at

www.chinausfocus.com. [Accessed on 22 July 2014]

Ho-fung, Hung. 2009. ‘America’s Head Servant?: e PRC’s Dilemma in the Global Crisis’, New Le

Review v. 60, nov./dec. [online] Available at: newlereview.org [Accessed on 5 April 2014].

ICF International. 2012. International Policies Impacting Energy Intensive Industries. United King-

dom. Available at: www.gov.uk [Accessed on 10 April 2014].

IEA (International Energy Agency). 2007a. Energy Policies of IEA Countries: e United States

2007 Review. Available at: www.iea.org [Accessed on 22 July 2014].

________. 2007b. World Energy Outlook: China and India Insights. Available at: www.iea.org [Ac-

cessed on 22 July 2014].

________. 2012. Oil & Gas Security: Emergency Response of IEA Countries. People’s Republic of

China. Available at: www.iea.org [Accessed 5 Abril 2014].

_______. 2011. World Energy Outlook. Available at: www.iea.org [Accessed on 22 July 2014].

Energy Security vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 661

Kerr, Lucas de Oliveira. 2012. Energia Como Recurso de Poder Na Política Internacional: Geopolitica,

Estrategia e o Papel do Centro de Decisao Energetica. PhD esis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande

do Sul, Brazil. Available at: http://www.lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/76222 [Accessed 15 April 2014].

Klare, Michael T. 2013. e Race for What’s Le. New York: Picador.

_______. 2008. Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: e New Geopolitics of Energy. New York: Metropo-

litan Books/Henry Holt.

_______. 2004. Blood And Oil: e Dangers And Consequences Of America’s Growing Dependency

On Imported Petroleum. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004.

_______. 2001. ‘e New Geography of Conict’, Foreign Aairs v. 80, n. 3: 49-61.

_______. 2000. ‘Resource Competition in the 21

st

Century’, Current History, n. 99.

Moore, Jason. 2011. ‘Ecology, Capital and the Nature of Our Times’, American Sociological Associa-

tion. Journal of World-Systems Research 17(1): 107-146. Available at: http://www.jwsr.org/wp-con-

tent/uploads/2013/02/Moore-vol17n1.pdf. [Accessed on 15 April 2014].

Morris, Lyle. 2012. ‘Incompatible partners: the role of identity and self-image in the Sino-U.S. rela-

tionship’, Asia Policy (13): 133-165. Available at: http://www.muse.jhu.edu/journals/asp/summary/

v013/13.mooris.html. [Accessed on 5 April 2014].

Murray, Brian et al. 2011. ‘e United States, China, and the Competition for Clean Energy.’ Policy

Brief, v. 11, n. 05 July 2011 [online] Available at: www.nicholasinstitute.duke.edu [Acessed on 5

April 2014].

Obama, Barack. 2013. Remarks by the President in the State of the Union Address. 12 Feb. 2013.

[online] Available at: www.whitehouse.gov [Accessed on 05 April 2014].

Pautasso, Diego and Lucas Kerr Oliveira. 2008. ‘Energy security of China and the reactions of the

USA’, Contexto Internacional, Rio de Janeiro (30) 2, May/Aug. 2008.

PEW - Charitable Trusts Foundation. e Pew Charitable Trusts. 2014. ‘Who’s Winning the Clean Energy

Race? 2013 Edition.’ [online] Available at: www.pewenvironment.org [Accessed on 10 April 2014].

Podobnik, Bruce. 2010. ‘Building the Clean Energy Movement: Future Possibilities in Historical

Perspective’. In: Kolya Abramsky (ed), Sparking a Worldwide Energy Revolution Oakland. CA: AK

Press. pp. 72-80.

_________. 2002. ‘Global Energy Inequalities: Exploring the Long-term Implications’, Journal of

World-Systems Research (8) 2: 252-274.

________. 2006. Global Energy Shis. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Raphael, Sam and Doug Stokes. 2010. ‘Energy Security’. In: Alan Collins (ed), Contemporary Securi-

ty Studies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Stokes, Doug and Sam Raphael. Global Energy Security and American Hegemony. Baltimore: e

Johns Hopkins University Press.

‘e Top 10 Countries Investing in Clean Energy.’ 2010. [online] Available at: http://www.upi.com/News_

Photos/gallery/Top-10-countries-investing-in-clean-energy/3200/ [Accessed on 10 April 2014].

U.S. Energy Infomation Administration. 2014. [online] Available at: www.eia.gov.

U.S.– China Joint Announcement on Climate Change and Clean Energy Cooperation. November

11, 2014. Available at: www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-oce/2014/11/11

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2002. O m do mundo como o concebemos. São Paulo, Revan.

662 vol. 38(2) May/Aug 2016 Steeves & Ouriques

_________. 2004. O declínio do poder americano. Rio de Janeiro, Contraponto.

World Bank. ‘China Overview.’ [online] Available at: www.worldbank.org [Accessed on 5 April 2014].

Xie, Tao and Benjamin I. Page. 2010. ‘Americans and the Rise of China as a World Power’, Journal of

Contemporary China (19) 65: 479–501.

Xing, Li and Woodrow W Clark. 2010. Energy concern in China’s policy-making calculations: from

self-reliance, market-dependence to green energy. Aalborg: Institut for Historie, Internationale Stu-

dier og Samfundsforhold, Aalborg Universitet.

Zweig, David and Bi Jianhi. 2005. ‘China’s Global Hunt for Energy’, Foreign Aairs Sept./Oct.

Acknowledgements

e authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and critiques that

proved vital to the nal version of this article.Also, thank youto Daniel Castelán and Graciela Di

Conti Pagliari for reading the text.

About the Authors

Brye Butler Steeves is a journalist, who has worked as reporter, writer, and editor at news-

papers, magazines, trade journals, and online. She is also the author of a children’s book.

Steeves recently worked as an economics editor for the Federal Reserve, and is now an

international aairs writer and editor. Her research interests include renewable energy

and interstate competition between China and the United States. Steeves has a bachelor’s

degree in journalism from Washington State University in the United States and a master’s

degree in international relations from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) in

Florianopolis, Brazil.

Helton Ricardo Ouriques is a professor in the Economics and International Relations

Department and in the International Relations Graduate Program at the Federal Uni-

versity of Santa Catarina (UFSC) in Florianopolis, Brazil. He is an economist and holds

a PhD in geography. Ouriques is a member of the World-Systems Political Economy Re-

search Group (GPEPSM). He is a professor of economic geography, geopolitics, the evolu-

tion of contemporary capitalism, political economy and the development of comparative

historical perspective. His recent research interests include: the development processes in

the countries of South America and western Asia (China, in particular); the paths of the

development of countries on the periphery of capitalism; and the geopolitical issues of

natural resources in the 21st Century.

Received on 28 January 2015, and approved for publication on 25 August 2015.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/